Every time you roast a turkey or bake bread, a fascinating chemical reaction gives your food its rich brown color, enticing aroma, and complex flavors. That reaction is called the Maillard reaction (pronounced my-ard), a cornerstone of both food chemistry and polymer science.

What Is the Maillard Reaction?

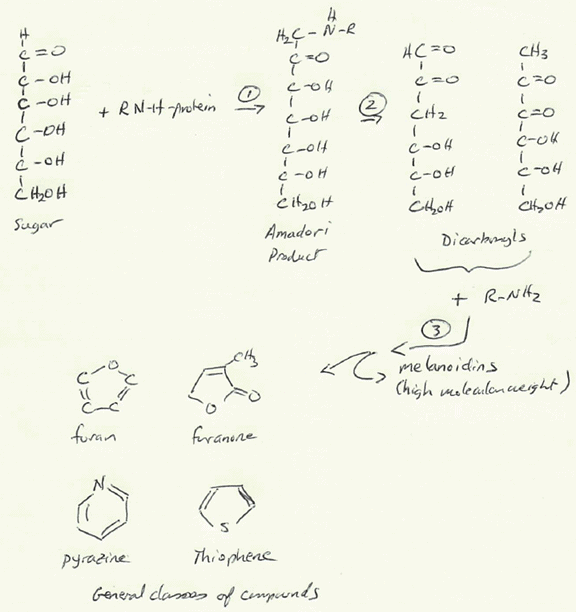

The Maillard reaction occurs when amino acids (from proteins) react with reducing sugars at temperatures above about 140 °C. It is not a single reaction, but a chain of them that unfolds in three general stages: initial, intermediate, and final.

- Initial reaction: Carbonyl groups from sugars react with amino groups from amino acids to form Amadori products, also known as glycated proteins.

- Intermediate reaction: These products break down into smaller molecules such as reduced sugars, dicarbonyls, and additional amino compounds.

Final reaction: Polymerization, condensation, and fragmentation reactions produce advanced glycation end products (AGEs), complex, often brown-colored molecules. These compounds have been implicated in diabetes, cardiovascular disease and a host of other potential issues.

Figure 1: Stages of the Maillard Reaction

The Role of Melanoidins

Among the many products of the Maillard reaction are melanoidins, a group of high-molecular-weight nitrogen‑containing polymers that give foods their brown hues. Their structures vary depending on the starting sugars and amino acids but generally include heterocyclic rings such as pyrroles, furans, and pyridines linked to a carbohydrate backbone.

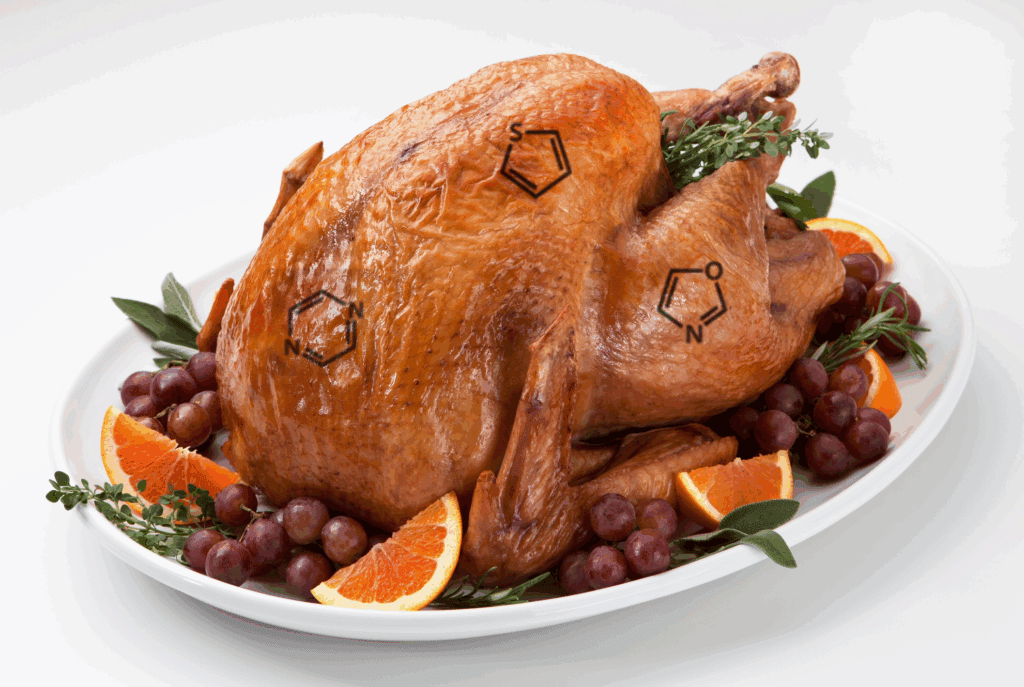

These same compounds are responsible for the characteristic color of roasted coffee, seared steaks, and baked bread. Melanoidins and other Maillard products also create the familiar flavor molecules that chefs prize:

- Pyrazines: roasted or toasted notes

- Thiophenes: rich, meaty flavor

- Furanones and furans: sweet, caramelized aroma

- Oxazoles and pyrroles: nutty or sweet nuances

Beyond the Maillard Reaction: Myoglobin and Color

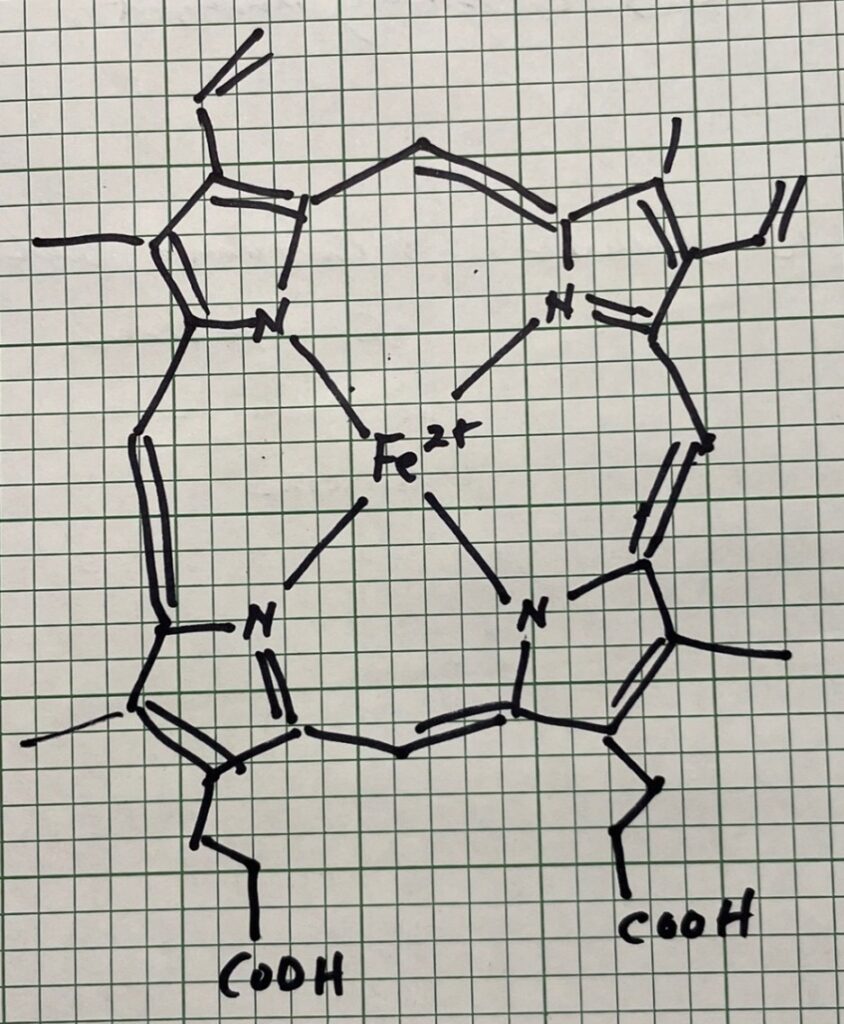

Not all browning in cooked meat comes from the Maillard reaction. Another source of the brown color is myoglobin, composed of 150 amino acids found in the muscle tissue of vertebrate animals (see Figure 2) and is used to store oxygen in muscles. Myoglobin has four pyrrole nitrogens that surround a ferrous ion center, as shown below. As meat heats, the heat denatures the protein and the myoglobin. This transition occurs much lower than the Maillard reaction (of the order of 60 °C) and is the driving force for the bulk color change that allows determination of “doneness” in red meat since the form of the converted myoglobin governs the final color of the molecule.

Figure 2: Myoglobin

How the Maillard Reaction Differs from Caramelization

The Maillard reaction should not be confused with caramelization, which involves the direct pyrolysis (thermal breakdown) of sugars without amino acids. Both processes create brown color and complex flavors, but they arise through distinct chemical pathways.

Let’s Talk Turkey: Maximizing the Maillard Reaction

When it comes to roasting a turkey, harnessing the chemical reactions involved in cooking makes all the difference in flavor and appearance. Here are a few science-backed tips:

- Dry the surface. Removing excess moisture by blotting helps the turkey brown more quickly.

- Use moderate alkalinity. Raising the surface pH with a small amount of baking soda encourages the Maillard reaction.

- Maintain high heat. A roasting temperature above 140 °C ensures the reaction proceeds effectively.

- Control heating rate and conditions. Although not relevant for surface browning, the rate of heating, and the oxygen environment (oven versus barbeque) can impact the color of the meat in the way that the myoglobin is degraded.

So do you need to be a chemist to cook a turkey? Thankfully, the answer is no, as all these reactions occur naturally just by cooking the turkey at the appropriate temperature and for the appropriate duration of time. However, when the author of this blog post was a graduate student in MIT’s Chemical Engineering department, the department secretaries received several phone calls every November from amateur chefs asking questions about how to cook their turkeys. The standard response from the secretaries? “Let us connect you to the Chemistry department.”